This post will focus on the concept of database narratives. When I came to this idea, it was practically entirely new to me. I had, to be fair, been exposed to some media that fell into this category in the past, but never recognised their correlations or formally identified the form.

Lev Manovich defines the database narrative as a form that does “not tell stories”.

[Database narratives] do not have a beginning or an end; in fact, they do not have any development, thematically, formally, or otherwise that would organise their elements into a sequence. Instead, they are collections of individual items, with every item possessing the same significance as any other.

— (2002)

Manovich goes onto suggest that a certain authority is taken away from the narrative and from the creative production team. Manovich likens the user of a database narrative to a film’s editing team, as the user becomes the one who constructs the order of revelations, the ordering of narrative elements into a sequence – the user becomes the storyteller (2002, pp. 218).

It’s important to note that other theorists also see database narrative existing in films and other platforms, where database narrative is not necessarily a form of user-based selection and ordering, but rather, one which draws specific attention to the “dual processes of selection and combination that lie at the heart of all stories” (Kinder 2003, pp. 6). She provides examples such as Groundhog Day (1993) and Pulp Fiction (1994), based upon their challenging of traditional chronological ordering.

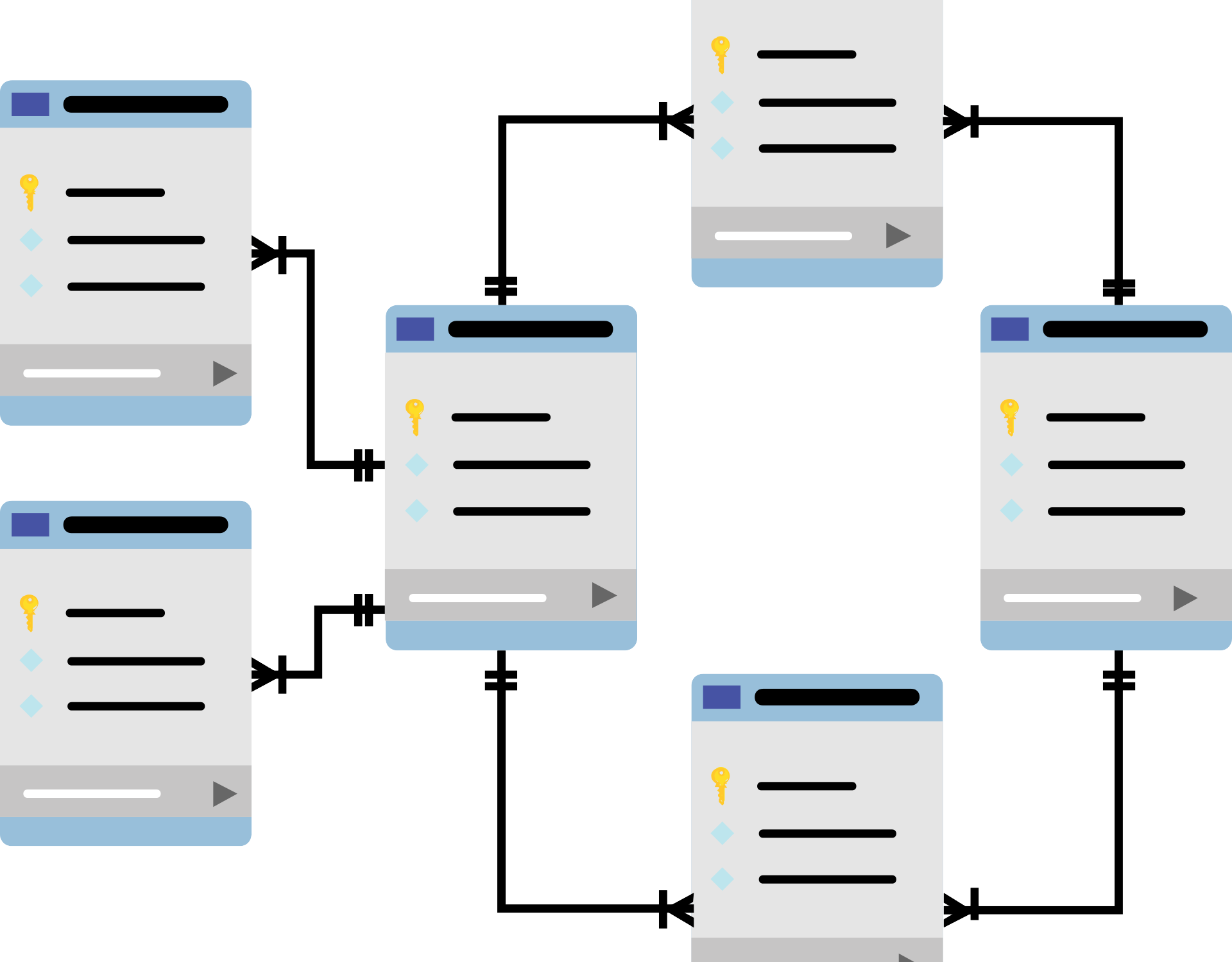

Another type of database narrative is the Rhizome narrative. Simply, the Rhizome narrative branches off into various possibilities of sequencing, but always begins and ends at the same point. Some examples are Waterlife (McMahon, 2009) and The Whale Hunt (Harris & Moore, 2007).

Learning about database narratives was fascinating. I love the challenge to traditional structure and sequencing. I wonder what John Yorke would think of Manovich’s idea that database narratives “do not have a beginning or an end”, since, according to Yorke’s theory, all narratives implicitly end up falling into that structure whether they like it or not. For example, does the time and/or date that the footage in the database was taken not affect a beginning and end? Once the user has played their part and ordered the content, are we left with a Yorkerian Five Act journey ‘into the woods’? Perhaps / perhaps not. This is all very new to me and would require more research and further thinking on the issue to draw any kind of conclusion. I struggle to see, however, the correlation between the two major theories of database narrative that have been discussed here. Manovich’s database narrative is a form based on digital dependency that allows the user to order sequences themselves, whereas Marsha Kinder calls Groundhog Day (1993) a database narrative because it exposes and draws specific attention to the process of selection. These seem to be different things. One is still very much controlled by the production/editing team and another is giving control to the user. I suppose it’s a slightly better term for Pulp Fiction (1994) than the vague ‘arthouse’ that the film is so often branded with, but should these two theories have their own names and qualifications, existing separately from and simultaneously to one another?

Works Cited

Harris, J., & Moore, A. (Directors). (2007). The Whale Hunt [Motion Picture].

Kinder, M. (2003). Designing a Database Cinema. (J. S. Weibels, Ed.) Future Cinema: The Cinematic Imaginary After Film, 346-353.

Manovich, L. (2002). The Language of New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

McMahon, K. (Director). (2009). Waterlife [Motion Picture].

Ramis, H. (Director). (1993). Groundhog Day [Motion Picture].

Tarantino, Q. (Director). (1994). Pulp Fiction [Motion Picture].

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

*Featured Image Credit:

Pixabay Creative Commons